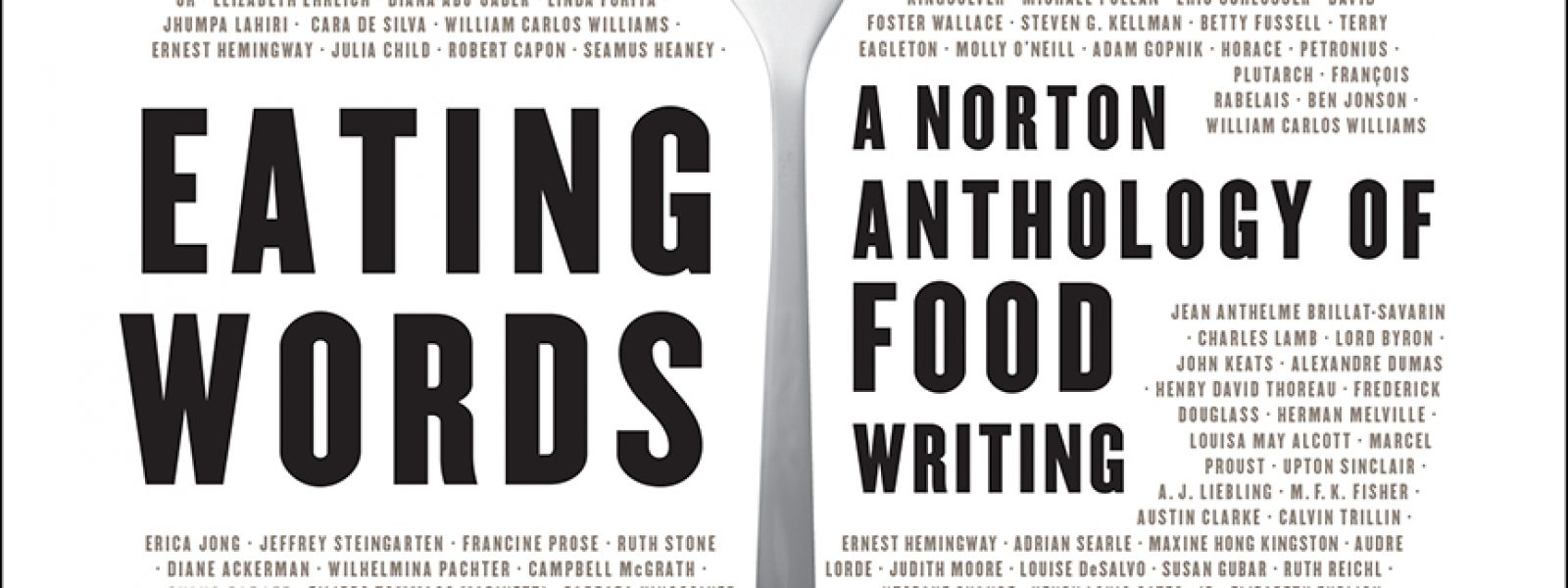

Eating Words: A Norton Anthology of Food Writing

Edited by literary critic Sandra Gilbert and professor and award-winning restaurant critic Roger Porter, Eating Words is a vast volume of exquisite food writing, from Biblical times through modern day. It’s a historically and conceptually diverse anthology, that goes beyond mere consumption and explores food’s relation to politics, psychology, anthropology and ethnicity. There are essays, poems, memoirs, satire, cookbook excerpts and manifestos, from writers such as Michael Pollan, Julia Child, Ruth Reichl, Plutarch, Henry David Thoreau, Gertrude Stein, Roland Barthes and Jonathan Gold, just to name a few. Below, Roger Porter discusses how they compiled the collection, characteristics of compelling food writing, and why we love to read about food.

AndrewZimmern.com: What’s your background and how did this book project come to be?

Roger Porter: I’m a professor of English literature at Reed College in Portland. I’ve been a restaurant critic, writing for Willamette Week and the Oregonian, for some 25 years and was nominated for a James Beard award for a restaurant review. I met my co-editor Sandra Gilbert in Paris at a dinner party. She’s a well-known feminist literary critic, one of the most important in the country. I had no idea when I met her that she was also very interested in food. A few years ago, she asked if I’d be interested in co-editing the Norton anthology of food writing, and of course I was very excited. We met for three years in Berkley to assemble the book. As you can imagine with a project as large as food writing, there were innumerable choices, and we had to struggle through what was allotted to us as a page count. We could have easily done three anthologies.

AZ.com: It seems like an impossible task. What was your process for choosing what to include?

RP: There are several anthologies of food writing, so we wanted to distinguish ours from the others. The first criteria—and it was an absolute—was that the writing had to be terrific writing itself. We also wanted to include a wide range of materials, both historically and conceptually. We wanted to have writing that was not just limited to descriptions of eating or food per se. We wanted food writing that would hit a nerve in the reader—echoes of childhood, echoes of memories of eating from the past, or writings that had a broad range of reference to political or psychological issues. In a broad sense, we wanted to include writings that were sensual, that were emotional, and in some cases intellectual.

The next task was to decide general sections for the book.We decided early on that we would have a section dealing with food writing from the earliest times, that’s why we started with Leviticus in the Bible. We led up in that section to Sinclair’s diatribe against the slaughterhouses and stockyards in Chicago around the turn of the last century. We have a section on ethnic tables, including memories of childhood and the ways in which food and ethnicity come together. There’s a section on the pleasures and the disgusts of food, that was in some ways the most fascinating one to include. It’s easy to define passages that speak to how enticing, exotic and revelatory a particular eating experience is, but we also wanted some selections that would really evoke food aversions. We have a wonderful essay by Peter Hessler on rat restaurants in China. It’s very funny, but also quite provocative. And along the same lines, a piece by Maxine Kingston, in which she describes her mother’s food preferences when she lived in China, culminating in her eating monkey brains. Incidentally, we had to eliminate a number of things we wanted very much; unfortunately we decided not to use a piece by Andrew Zimmern, in which he eats the entrails of the Samoan fruit bat.

We have a section on kitchen practices and what it means to actually cook things in the kitchen, and we included a section on food politics. I think the culinary is often political. There’s a wonderful, quite unknown book we excerpted from, called The Futurist Cookbook, written early in the 20th century by an Italian fascist who believed that your mental outlook could be contaminated by bad food. Of all things, he decides that pasta makes Italians soft. He has a manifesto against pasta; it’s very funny. Lastly, we have a section on cultural tables, a kind of anthropology of food.

AZ.com: During the 3-year process of compiling this book, what took you by surprise?

RP: One of the things we found surprising was how contemporary the historical writing was. Some of the prohibitions and taboos from biblical times lead, in some sense, directly to contemporary writings like the manifesto from PETA. Plutarch the Roman writer says ‘animals kill to survive, we kill for appetizers.’ It’s a very contemporary feeling. There’s a lovely piece by Frederick Douglass, the great African American writer, that lauds a favorite recipe by slaves of cornbread and he contrasts it to the kind of decadent eating of the slaveholders. It’s a very political and emotional attack on decadent eating by someone who had been a slave for many years.

One of the things we found really wonderful was that writers who came upon new foods for the first time, often wrote about the foods as if they were discoveries of a new world. They went beyond just the mere sensuality of it. This short selection from the Korean-American novelist Chang-rae Lee exemplifies this. He writes about the time he discovers a sea urchin as a young teenager.

“I point to a bin and I say that’s what I want—those split spiny spheres, like cracked-open meteorites, their rusty centers layered with shiny crenellations. I bend down and smell them, and my eyes almost water from the intense ocean tang. ‘They’re sea urchins,’ the woman says to my father. ‘He won’t like them.’ My mother is telling my father he’s crazy, that I’ll get sick from food poisoning, but he nods to the woman, and she picks up a half and cuts out the soft flesh.

What does it taste like? I’m not sure, because I’ve never had anything like it. All I know is that it tastes alive, something alive at the undragged bottom of the sea; it tastes the way flesh would taste if flesh were a mineral. And I’m half gagging, though still chewing; it’s as if I had another tongue in my mouth, this blind, self-satisfied creature. That night, I throw up, my mother scolding us, my father chuckling through his concern. The next day, my uncles joke that they’ll take me out for some more, and the suggestion is enough to make me retch again.

But a week later I’m better, and I go back by myself. The woman is there, and so are the sea urchins, glistening in the hot sun. ‘I know what you want,’ she says. I sit, my mouth slick with anticipation and revulsion, not yet knowing why.”

It’s a wonderful piece of writing. It’s so vivid. Julia child is a classic example of this as well, when she eats her first Sole Meunière in France. At the time, she didn’t even know what a shallot was. She knew almost nothing about food, and this discovery of course transformed her life, and ours in some ways.

AZ.com: Why do we read food writing?

JP: We thought a long time about this. There’s always been three major subjects people either love to talk about or think it’s impolite to talk about at the dinner table: religion, politics and sex. Now, I think food is right up there. We cannot resist talking about food. There are food blogs, the food channel, food films; food is everywhere in our culture. The question is why. There are two ways of thinking about it. One is the doubling of pleasure—we like to eat and we like to talk about eating. Food writing is also a substitute for the real thing. There’s so much talking about food, yet people aren’t doing that much cooking. They’re buying cookbooks, but they’re not actually using them. So why do we read about it? I began to think about the phrase ‘food porn.’ It usually refers to gorgeous, hedonistically enticing photographs of food. Anthony Bourdain often shows close ups of pulsating ingredients and oozing flesh on his show. What is it about this that attracts us? Pornography, in its sexual aspect, is about the way in which desire is simultaneously aroused and kept at a distance. It’s something that seduces us, but we can’t have. I think a lot of food writing has that quality. We get pleasure out of reading about food, but we don’t necessarily have it. It’s a very complex psychological phenomenon, and I’m not quite sure I am really equipped to understand the nuances of it.

AZ.com: As we become more obsessed with food, are people writing about it differently?

RP: I think people writing about food now can take a lot more for granted. The public is more knowledgeable. You see it very dramatically in restaurant reviewing. The reviewers in the New York Times, or in newspapers in general, don’t have to explain particular ingredients. They just assume the readers will understand. I think the same is true with more general food writing. It assumes a more cosmopolitan audience. We travel more, and we travel in order to eat.

AZ.com: What type of food writing do you find most compelling?

RP: Writing that takes in other aspects of life, that is not just about consumption, but that really explores food’s relation to a whole host of things. I don’t write restaurant reviews any more, but when I did, I always tried to be an amateur anthropologist of food. I would talk about the nature of the cuisine, and not just about the dishes themselves—nothing is more boring to read than descriptions of dishes. The vocabulary very quickly gets limited and worn out. I think the same thing is true in my appreciation of good food writing; I think it goes beyond consumption. In his recent book about food, Adam Gopnik says that the table is a place where all sorts of things come into play—family, memory, relationships. It draws people together. We tried to get that kind of writing into the book in every way possible I think.

AZ.com: Is there a particular selection in this book that really informs us of a time and place?

RP: There’s a piece by Anya von Bremzen, called The Émigrée’s Feast, about Russian cooking in the 20th century. Von Bremzen’s mother tried to replicate in her New York apartment great feasts from the period of the czars, prior to the Russian Revolution. It’s a fascinating essay because it’s deeply nostalgic. It connects food to her personal memories, incorporating history, politics, and a sense of a childhood that is recoverable.

The French writer Roland Barthes wrote a book on his trip to Japan called Empire of Signs. In it, he makes a wonderful distinction between the use of chopsticks in Japan and the way in which we attack food with a knife and fork in the West. If we have a piece of meat on our plate, he says, ‘we gouge and chop, and rip and tear.’ He contrasts that with the Japanese use of the chopstick, describing the act of picking up the morsel of food with chopsticks as very delicate. He goes on to develop this metaphor, comparing it to a mother animal picking up its young by the scruff of the neck, never harming the young. It’s not a piece about food, it’s a piece about eating, about technique, and it absolutely captures two different cultures. It’s a lovely recognition of difference.

AZ.com: What is one of your favorite pieces?

I’d like to read a poem by Seamus Heaney, entitled Oysters.

Our shells clacked on the plates.

My tongue was a filling estuary,

My palate hung with starlight:

As I tasted the salty Pleiades

Orion dipped his foot into the water.

Alive and violated

They lay on their beds of ice:

Bivalves: the split bulb

And philandering sigh of ocean.

Millions of them ripped and shucked and scattered.

We had driven to the coast

Through flowers and limestone

And there we were, toasting friendship,

Laying down a perfect memory

In the cool thatch and crockery.

Over the Alps, packed deep in hay and snow,

The Romans hauled their oysters south to Rome:

I saw damp panniers disgorge

The frond-lipped, brine-stung

Glut of privilege

And was angry that my trust could not repose

In the clear light, like poetry or freedom

Leaning in from the sea. I ate the day

Deliberately, that its tang

Might quicken me all into verb, pure verb.

I think that’s a great ode to the sensuality of eating, but also has some nice references to Romans eating those oysters. It’s a kind of continuity through time and space.

About Roger Porter

About Roger Porter

Roger Porter has been Professor of English at Reed College, in Portland, Oregon, for many years. He specializes in Shakespeare, Modern Drama, Modern Fiction, and Autobiography. He is the author of Self-Same Songs: Autobiographical Performances and Reflections, and Bureau of Missing Persons: Writing the Secret Lives of Fathers. He has been a restaurant critic in Portland for 25 years, and was nominated by the James Beard Foundation for outstanding restaurant criticism.