Exploring the World Through Food

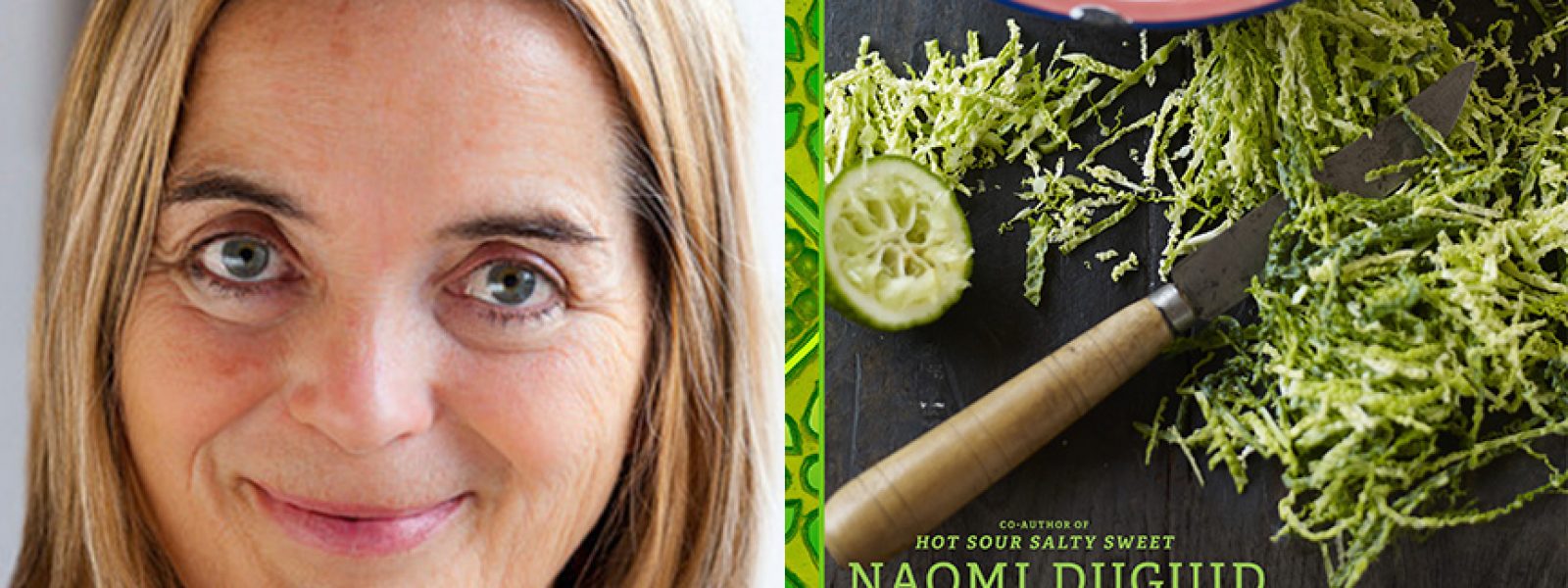

Naomi Duguid is a culinary anthropologist, translating her cultural encounters abroad into stories, photographic essays and recipes for the adventurous cook. A writer, photographer, traveler and cook, Naomi has co-authored six award-winning books including Hot Sour Salty Sweet: A Culinary Journey Through South-East Asia and Beyond the Great Wall: Recipes and Stories from the Other China. Her latest book, Burma: Rivers of Flavor was named best Food and Travel Cookbook by the IACP. Below, Naomi talks about the characteristics of Burmese cuisine, engaging with locals through food and what’s next.

AndrewZimmern.com: How has traveling shaped who you are?

Naomi Duguid: It’s made me more appreciative of the every day, of the good luck I have to be able to travel, to be able to go somewhere that is a difficult or totalitarian place, or a place where local people have less freedom, and try to understand it and engage with the people, but also have the freedom to leave again and to think freely. It’s given me an appreciation of how creative human beings are, whatever their situation. The more difficult the situation, the more creative people are pushed to be in order to survive and that’s a remarkable thing. I end up with a huge respect in a general way for human kind, just a feeling that I’m lucky to be able to connect with human beings on the ground in different cultures.

AZ.com: Did your interest in food grow out of your love of travel?

ND: I’m really interested in food as a way of illuminating what people have. It’s a way of understanding culture, a way of understanding how people live and how they think about things. For me, food is a window. It’s a lens. Some people see food where I don’t see food at all, and vice versa. Often there’s something that looks to me like food and for them it’s absolutely not food, like Tibetans don’t eat fish. For them it’s disgusting. That’s a really interesting thing, so I find it a fabulous thread to connect us all and for me to learn from.

AZ.com: Why did you choose Burma for your latest book?

ND: I worked with my now ex, Jeffrey Alford, on a number of books in the region. We worked on a book about South Asia, and I was in Bangladesh for that book. Then we worked on Hot Sour Salty Sweet and there are some Shan recipes in that book, people who live in Burma and northern Thailand. We had been with the Karen rebels on the Burmese border. Also, the book Beyond the Great Wall deals with Yunnan that borders Burma, so really it was just a keystone place that needed to be engaged with. It took a little bit of ‘take a deep breath and duck dive,’ because there was this notion that it was going to be hard, people were going to be tightened up, the government was tight. Once I went in for my first trip, got my visa, and got to outlying areas that had been closed earlier and were open, I just thought, ‘this is doable.’ I just had to keep building in this patience. Burma was not the first time I’d been in a place where it was necessary to gage the feel on the street and in the market, and give people time to get used to me.

AZ.com: How do you go about gaining people’s trust and researching recipes?

ND: There are particular challenges in different places and cultures. I was in Burma before it was a more loosened up place, and so people were living in a somewhat fearful, cautious way. If they hung around talking to a foreigner, they might easily be questioned afterwards by the police. People were really cautious around me at the beginning, so my biggest ingredient is time. I hang around taking pictures in the market of everyday ordinary things, and by about the third day people recognize me as that odd foreign woman who seems to be interested in boring old foods, and they sort of relax. Then there’s a human connection, they see me as a person. When I traveled earlier with my kids, there was more intimacy in the sense that they could see me. I’m seeing them in their home situation, say with their kids or spouses, and they were seeing me that way, so that’s a more immediate connection. That opens doors in the sense that it relaxes people, it’s more equal and fair. My job is to give them enough time to get a read on me.

And then I just eat a lot. I eat all the time, just tasting things, asking questions at the market. I never actually ask for a recipe. There isn’t such a thing anyway. I watch people make things. And in a place like Burma you can’t take notes in public, because that’s again like you’re a journalist and I would have been kicked out of the country if they thought I was a journalist. My note-taking device was my camera. Sometimes I would get invited home by people and that’s a real luxury because then everyone’s relaxed, so we can kick back and I can take notes.

I also watch people. Gesture is important in terms of technique. Watching people over and over again making food on the street is a fabulous way to learn. You just sort of absorb the gesture. I have people come do a cultural immersion in Chiang Mai in northern Thailand every January. I want them to get body memory for certain types of techniques and gestures. We start on Sunday night, and by the time they’re cooking by themselves on Friday, they’re confidently using cleavers in a Thai village way; they are confidently using mortar and pestle in that way. They’ve absorbed the body memory of it. Cooking is very practical, that’s the wonderful thing of it. You are not only learning with your head, your eyes and your heart, but you’re actually learning with your whole body. So, it’s a mixed bag, but the biggest ingredient is time, patience and empathy.

AZ.com: How do you recreate the recipes at home? How long does that typically take?

ND: It’s a lottery. Some will come together on the first go; others will take several runs. The hardest one of all was injera for the flatbread book. That was 10 tosses, and eventually I got it. Sometimes I do give up, if it’s tricky given North American equipment, the absence of a clay pan for example, then maybe I just can’t put it in the book. I’m asking people to embark on cuisines that are remote to them, so I need them to build confidence from the first thing they try, so they will try another and another. I want them to feel connected and get their sea legs. Sometimes I can adjust things as I go along, like a Burmese salad. That’s an easy one because it’s a composed dish, once I figure out proportions and balance, I can pretty well get it in one or two goes and then rerun it several times or have a friend test drive it for another eye, another palate.

AZ.com: What are the defining characteristics of Burmese cuisine?

ND: The first characteristic is that there isn’t just one cuisine. There are central Bamar people who are 70 percent of the population, that’s the dominant cuisine. The Shan people have an incredible repertoire, and some of that is filtered into central Burmese. The Rakhine on the West Coast have a related repertoire, but again with differences. The Kachin people, a completely different people in the far north, have a fabulous repertoire of food that has almost no relation to the aesthetics and the methods of central Burmese. In southern Burma, the food is more like the Muslim food in southern Thailand.

The cuisine comes out of the climate and the people. You have fish sauce, and that applies to the people along the coast and in central and southern Burma, but not to the mountain people, not to the Kachin and the Shan. People cook in peanut oil because there are a lot of peanuts there, it is the main cooking medium. There’s not as much, generally speaking, chili intensity as in Thai food. Also there’s turmeric and shallots. In central Burmese cooking, shallots are the rule. If you’re making a curry, you heat the oil, add some turmeric, always a pinch of turmeric, and then add chopped shallots and that gives it sort of a sweet undernote that starts your dish. Shallots are also fried in oil to make crisp sweet things that you add to a salad last, as you might add a crouton. And then the oil that you fried those shallots in also becomes flavor and you drizzle a little of that on the salad.

I think the salads are the most brilliant and distinctive achievement in central Burmese and Shan food. They are just fabulous. The salads are a really light handed balance of textures and flavors. The Shan people also make brilliant use of, and so do the central Burmese, chickpea flour. That’s really a whole other interesting area to explore.

The Kachin have remarkable dishes. Their food is infused with fresh herbs and is often steamed, so there is an intensity of flavor because things are not fried. There’s a pounded-beef recipe in the book that’s just a killer. It’s so remarkable, and so unlike anything else. So it’s really diverse.

AZ.com: How long did you work on this book?

ND: For the book I did eight or nine trips, two or three a year. I wanted to start in the fall of 2008, but there were demonstrations in Thailand and the airports were closed. I couldn’t get out of Thailand and into Burma, so I made my first trip for the book in early February of 2009.

AZ.com: Do you have another project in the works?

ND: Yes, I have another book in the works that is hopefully coming out in 2016. I’m working on culinary cultures that have been touched by Persian culinary culture, so Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iraqi Kurdistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Iran, and so on. There are a lot of peoples in there that we in the West sort of generalize. We’ve lost track of a lot of really amazing food. People have come to know about Georgian food a bit, but there’s a lot more, and a lot of historical cross threads that are really fun to pursue.

Check out Naomi’s recipe for Kachin Chicken Curry.

Naomi Duguid, traveler, writer, photographer, cook, is often described as a culinary anthropologist. Her most recent book Burma: Rivers of Flavor (Artisan, 2012) celebrates the food cultures of Burma in recipes, stories and photos. Burma was named best Food and Travel Cookbook by the IACP (International Association of Culinary Professionals)

Naomi is the co-author of six previous books of food and travel, all award-winning: Hot Sour Salty Sweet: A Culinary Journey Through South-East Asia; Seductions of Rice; Flatbreads and Flavors; Mangoes and Curry Leaves; HomeBaking; and Beyond the Great Wall: Recipes and Stories from the Other China.

Naomi is a contributing editor of Saveur magazine, has a bimonthly column “Global Pantry” in Cooking Light magazine, writes a weekly blog, www.naomiduguid.blogspot.com, and conducts food-focussed tours to Burma and intensive cultural-immersion- through-food sessions in northern Thailand each winter (see www.immersethrough.com).