An Exploration of Bitter

A James Beard award-winning author, Jennifer McLagan is known for challenging her readers, delving into topics that make us rethink what we eat and why. She’s famously covered Bones, Fat and Odd Bits, each a single subject book with recipes that aims to revive an unloved ingredient. McLagan’s latest book is Bitter, a fascinating look into the science, culture and history of an underrated and misunderstood flavor. We talk with McLagan about her contrarian nature, supertasters, and how bitterness is important to the human body.

AndrewZimmern.com: What inspires you to tackle topics that many people are averse to… fat, bones, odd bits, now bitter?

Jennifer McLagan: Perhaps it’s my contrarian nature? Bitter, like bones, fat and odd bits is another unloved topic, too often seen as a negative, it deserved rehabilitation. With each of these topics I believe that people are only averse to them because they don’t know them, understand how to use them, or realize how good they are for both your cooking and your health. In each case I’ve been proved right, I felt especially vindicated when Time magazine’s cover story announced this year that animal fat was good for you.

AZ.com: You write that bitter taste is complex and subjective. How would you describe bitter and what experiences have led to your conclusion?

JM: I think bitter is the most interesting taste, as we can’t seem to agree on it. Only acids signal sour, but thousands of different chemicals elicit a “bitter” response. This makes bitter an elusive flavor that is hard to pin down. It encompasses such a wide range, from subtly bitter celery leaves through to extremely bitter melon. What I find bitter you may not and vice versa. We easily agree on what is salty, sweet, acidic, and probably even umami, however bitter is much harder to define. Bitter is not simply a reaction on our tongue—a taste in the strict sense—but also includes many different signals that register as bitterness in our brain.

AZ.com: Why do some people experience bitterness more intensely than others?

JM: How we perceive bitterness is influenced by our genetics that can make us more sensitive to bitterness. About 25 percent of the population is highly sensitive to bitter tastes; this group is often called supertasters. Some of us have more taste buds on our tongue, which makes us, like babies and children, highly sensitive to bitterness. Also our culture, experience of food, peer pressure, and our environment all influence how our brain determines bitterness. We are all living in our own separate taste worlds.

AZ.com: How is bitterness embraced by different cultures? Why do you think it’s just now showing up on menus in the United States?

JM: Traditional Chinese medicine uses many bitter plants and herbs and many Asian cuisines have an appreciation of bitterness. They know bitterness often signals foods that are very good for you and they often incorporate bitter foods into their cooking. Chinese and South Asian cooks love bitter melon and believe it cleanses the body. Research shows that it lowers blood sugar levels, fights viruses, and a study at the University of Colorado Cancer Center showed that bitter melon juice also kills cancer cells. The Italians also love bitterness; they eat bitter vegetables and enjoy bitter drinks, like Campari and amaros. In North America, bitter is making its way onto menus thanks to the revolution in the cocktail world. Bitter cocktails are more popular than ever, bitter European aperitifs are common and just look at the number of handcrafted bitters you can buy. Bitterness in the kitchen is the next step.

AZ.com: While writing and researching this book, what surprised you about bitter ingredients, taste and flavor?

JM: I was surprised by how hard it is to define what is bitter (see above) and I also learned a lot about how we perceive flavors. We all learn that our tongue detects taste and with the addition of smell creates flavor. However, I discovered how our brain uses all senses especially sight to determine flavor. Everything from the color of your drink to the pitch of music playing when you drink it can determine your perception of how bitter you think it is.

In the eighteenth century we had eleven basic tastes, so why do we narrow it down to just five or six today? We need to expand the way we think of taste and we also need to improve our vocabulary of taste so we can describe it better.

It was fascinating to learn that bitter receptors are not confined to our tongue; they are in our throat, digestive tract, intestines and most surprisingly, our lungs and (for some of us) our testicles. They all respond to bitter chemicals in different ways. It shows how important bitterness is to our body’s function.

AZ.com: What are some common misconceptions of bitter?

JM: When you use bitter foods people often think that the dish will taste bitter. Yes, you can make a dish taste bitter, but bitter is important in balancing, and adding complexity to a recipe. Often you don’t realize its importance until you remove it. A good example is caramel. No one thinks of caramel as bitter, but the best caramel has a touch of bitterness, which makes it more complex and less sweet. Although bitter can signal toxins most of bitter foods we consume are not poisonous, they are good for you.

AZ.com: What’s next?

JM: I don’t know yet. I like the single-subject cookbook because exploring one topic takes you into interesting places, but it’s a lot of work. I enjoyed my summer off so much that I think I will take the winter off too. I plan to go out to the west coast with this book for a week, and then to Australia.

AZ.com: What’s in your fridge?

JM: Homemade tonic water, butter, duck fat, lard, duck confit, mustard, eggs, unhomogenized milk, coffee, white wine, a veal kidney, olives and of course bitter greens.

Get McLagan’s recipe for Radicchio & Pumpkin Risotto from her new book Bitter.

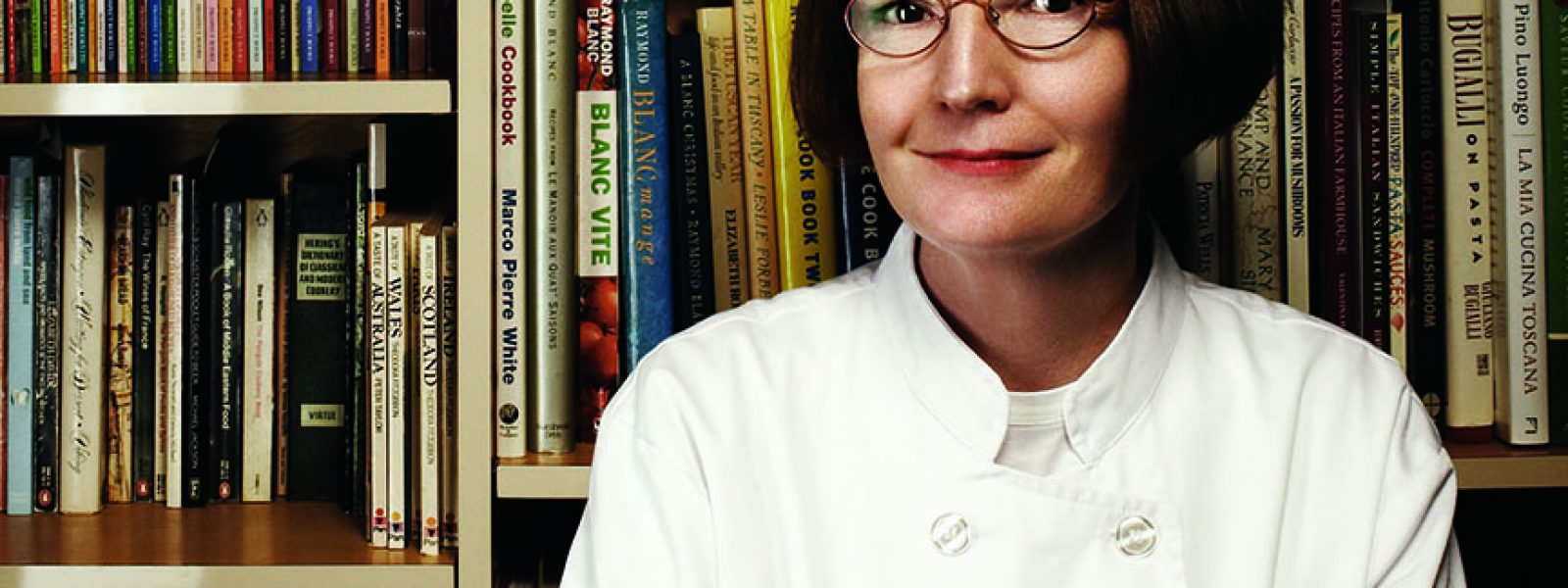

About Jennifer McLagan

JENNIFER McLAGAN is a chef and writer who has worked in Toronto, London, and Paris as well as her native Australia. Her award-winning books, Bones (2005), Fat (2008), and Odd Bits (2011), were widely acclaimed, and Fat was named Cookbook of the Year by the James Beard Foundation. Jennifer has presented at the highly prestigious Food & Wine Classic in Aspen, the Melbourne Food & Wine Festival master class series, the Epicurean Classic in Michigan, the Terroir Symposium in Toronto, and the Slow Food University in Italy. Jennifer divides her time between Toronto and Paris. To learn more, visit www.jennifermclagan.com.

JENNIFER McLAGAN is a chef and writer who has worked in Toronto, London, and Paris as well as her native Australia. Her award-winning books, Bones (2005), Fat (2008), and Odd Bits (2011), were widely acclaimed, and Fat was named Cookbook of the Year by the James Beard Foundation. Jennifer has presented at the highly prestigious Food & Wine Classic in Aspen, the Melbourne Food & Wine Festival master class series, the Epicurean Classic in Michigan, the Terroir Symposium in Toronto, and the Slow Food University in Italy. Jennifer divides her time between Toronto and Paris. To learn more, visit www.jennifermclagan.com.